Maurice - Forced to wear the German Uniform

His father destined Maurice to become a farmer. During his childhood he worked the fields, gathered fodder for the animals, and helped in the bakery when he wasn't he attending school.

On July 10, 1939 the family was blessed by the birth of a son they named Gerard. As a 24 year old husband and father, Maurice would endure two years of Hell on the Russian front wearing the despised German Army uniform. He was lucky: nearly all of the region’s draftees became cannon fodder on the Eastern Front; over 20,000 of them are still missing including his brother Julien.

I have written this story combining several narratives that Maurice wrote and information from a book that his son Norbert authored. Red lettering will indicate notes added by myself for greater understanding.

Maurice's Story

|

| Maurice on his bicycle |

I asked to stay in the neighborhood. I was assigned to a position in Sélestat (172nd Fortress Infantry Regiment) where I performed my 2 years of required service from September 2, 1936 to September 1, 1938. Sélestat was only 5 miles away; I had a bicycle so I often was able to go home. My brother Marcel was in Algeria doing his military service at the same time.

The Fall of France - June 1940

I had finished my military service when the war broke out. In September 1939, I was recalled and assigned to an underground fortification on the Rhine River near Marckolsheim about 12 km from our house. I was one of 17 infantrymen assigned to blockhouse 40-1, called du Sponeck (part of the 42nd Infantry Regiment).

|

| Maurice is in the middle of the back row |

"Until that morning, we had never fired a shot. The night before the commander we had informed us that we were henceforth authorized to fire the mortar 60, which we were told was a secret weapon. On the morning of 15th, I noticed that the reed screen that has always obscured the front of bunker had disappeared, which I reported to my leaders.

Suddenly the Germans opened fire. A deluge of PAK shells (Panzer Abwehr-Kanone = anti-tank cannon) hit their target and shook the concrete and our nerves. The structure was shaking on its foundation; the concrete was cracking and trickled down the walls. We were overwhelmed by the smoke. At nine o'clock, the steel bell that covered the structure was pierced. One of our comrades lay at our feet, seriously wounded. A fire started in a corner of a mattress and we choked on the smoke; our weaponry was useless. In any case, the cloud of smoke or artificial fog - I do not know which - that surrounded the blockhouse was so dense that we couldn’t see anything to shoot.

We never saw our attackers. We were ordered to hold our position at all costs; a counter attack would follow, with the support of tanks and planes. The wind. The situation had become untenable and we evacuated the structure before it collapsed.

At 10 a.m. the shelling began. The brutality of the fire fight was a surprise. The shoreline structures were reduced to silence and the enemy began crossing the Rhine. Until night, they fought in the Rhine forest.

At 10 a.m. the shelling began. The brutality of the fire fight was a surprise. The shoreline structures were reduced to silence and the enemy began crossing the Rhine. Until night, they fought in the Rhine forest.On June 16th, the enemy emerged from the dike. We fought all day; when evening came the fallback order was given. On the June 17th we withdrew to the Ill river, then to Kaysersberg and finally the order was given to the men of 42nd to make a stand by Le Bonhomme near Xonrupt in the Vosges mountains. We were ordered to defend the crest of the Vosges to the north and south of the gorge.

However, on the night of 19th there were reports of infiltration by the enemy in various parts of ridges. The 42nd was then at Col de Surceneux to the northeast of Xonrupt.

It was on the 20th that attacks by the Germans threaten to overcome the defenders of the pass. Further retreats were made to Saut des Cuves and ultimately Gerardmer. On June 22nd at ten o'clock "Cease Fire" was given. I was taken prisoner by the Germans; one month later they freed us.

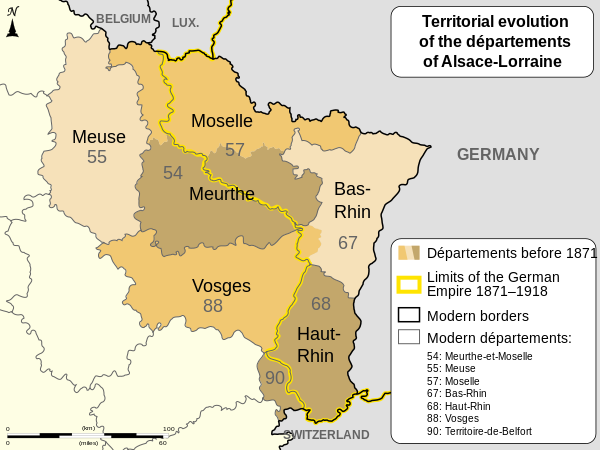

Drafted into the German Army

After the Fall of France, the Germans began the Nazification of Alsace. For years Maurice and his family endured the forced changes; including changing his from from Maurice to Moritz. In August of 1942 the regional military governor of Alsace Robert Wagner ordered the forced conscription of Alsatian men into the Wehrmacht (German Army). In October 1942, young men born between 1922 and 1924 were drafted, which included Maurice's younger brother, Edmond.

Maurice and his brother Julien were drafted into the German army on April 19th, 1943 in a second wave of forced conscription. Maurice was a 24 years old and a father of a 4 year old. He was shipped to Chemnitz in Saxony where he said he received very strict military instruction.

On May 9th, he was transferred to Jarosław, Poland for additional training and assigned to the Adolf Hitler Kaserne barracks. Due to censureship rules, Maurice was unable to write about his training in letters but said that Chemnitz was a breeze in comparison. From there he was transferred to Mielec, in the Krakow district of Poland. Maurice would tell his family that the Poles were very poor but strong believers that when the soldiers were prohibited from going to mass, they went there secretly.

|

| Maurice on right in Poland |

On May 9th, he was transferred to Jarosław, Poland for additional training and assigned to the Adolf Hitler Kaserne barracks. Due to censureship rules, Maurice was unable to write about his training in letters but said that Chemnitz was a breeze in comparison. From there he was transferred to Mielec, in the Krakow district of Poland. Maurice would tell his family that the Poles were very poor but strong believers that when the soldiers were prohibited from going to mass, they went there secretly.

Fighting on the Eastern Front

In November 1943 Maurice was sent to the Russian Front near Vitebsk (city in northeast Belarus), Memel (Memel is today known as Klaipeda, Lithuania). Maurice would write:

"We were transferred to Zwickau (in Saxony) where the Marschbataillon was formed, and on November 27, 1943 we marched through Zwickau singing. When we arrived at the station our battalion was loaded into cattle wagons. None of us knew the destination, but we understood very quickly that we were heading east. On the 30th of November we landed in Warsaw, and on the 3rd of December we were deposited near Newel, north of Vitebsk, in Russia, and dispersed into the combat units. There were no more than three Alsatians per company, the rest were Germans. 10 days later we were surrounded by the Russians.

The winter was well underway; there was a meter of snow on the ground when we reached our trench. Morale fell very quickly when when those who were already there were astonished at the arrival of reinforcements since they were practically surrounded by the enemy. That night, in our trench, by the light of a candle, everyone rushed to write home, to give his new address; almost everyone had wife and children at home.

So it was with me, on the 7th of December 1943, I wrote to my wife Jeanne: "Es ist Krieg, seit gestern Abend sind wir im Graben" (We’re at the front; we’ve been in the trenches since last night).

The enemy in front of us howled non-stop, for there were Mongolians in their ranks. The following days we were frequently attacked, and the pincers closed more and more, so that on the evening of December 15, 1943, we were ordered to pack up and retreat. There was a snowstorm. When we arrived at the company's command outpost everything was set on fire. Everything left behind was to be burned. We were given our orders; at 1 am, we were to break through the encirclement during the night. We had to leave our gear behind, keeping only our guns and ammunition, in order to advance in the thick layer of snow.

|

| WWII Russian mounted soldier |

Everything was upside down when the sun rose. The company commanders reassembled their men under a shed, our lieutenant succeeded in gathering 16 men from our company. When he spotted me, he took me aside to tell me of his amazement at seeing me return, he thought I had fled to the Russians, since I had been declared politically unreliable.

|

| German soldier in Russia |

That night we all sat around a table and every one wrote home. In my letter I inserted a small fir branch and the label from the champagne bottle, which is still carefully preserved among the 374 letters from Russia. How great was my joy when that same day I received my first letter from Mussig. Everyone was crying at the sign of letters from home, even more since it was Christmas Eve.

But the events took a different turn; by 9 o'clock the next morning the noise of the Russians preparing for battle pierced the air. We were loaded onto trucks and driven to the front. In the truck the air was silent; most of us prayed and thought our homes, and our families who were celebrating Christmas at the church.

| 1944: Three German soldiers covered in snow and ice |

There was nothing new on New Year's Eve. At morning call the sergeant asked for volunteers for a shock troop (Stosstruppe – assault team) for the evening. They were to seek contact with the enemy. Naturally there were no volunteers; 15 men were appointed. The list was posted at noon, and my name was among them. I thought this time it was all over and I lay down in the straw to pray. When the sergeant passed, he simply told me that it would be of no use to me: "Das kann dir nicht helfen", (That cannot help you). We were told there would be nothing to eat, in case someone was injured in the intestines.

|

| Desperate conditions on the Eastern Front. German troops on the march, a Panzer III |

Late in the night, when silence had returned, we snuck back with the dead comrade and the wounded sergeant on our sled. It was three o'clock in the morning, we were exhausted and our thoughts were empty. We remained in the trenches from 2nd to the 7th of January, 1944, "After this offensive was the retreat, what a picture that was."

Towards Easter we found ourselves in the trenches near Lake Polota. There was still a lot of snow but it was less cold. We didn’t have a bunker, just small burrows in the trenches, and only small candles for a little light. We weren’t allowed to make a fire unless the temperature was below 36 degrees.

At the beginning of Holy Week a military chaplain came to visit us when it was pitch dark. It was the first time, and he came to raise our spirits. Two days later we were again alerted for possible attack by the Russians, and it was necessary to be ready, day and night.

|

| German troops march past a Tiger tank, on the Eastern front, January 1944 |

The non-commissioned officer who ran the machine gun was wounded in the shoulder by a bullet, and his machine-gun was defective, and yet he would not retreat. To my right I heard screams. In our area the enemy had difficulty breaking through our very active artillery, and they had many losses. Yet we saw them coming slowly towards us.

|

| German infantry in the trenches on the Eastern Front |

On the same day at 4 pm, our troops went on counter-attack with tanks, to recover the dead. But without us, for we were all shocked and dejected by the death of our comrades. There were 17 deaths and 2 missing in our company.

On 6 May 1944, it had been 6 months since I had been on leave, and on 11 May we were about 30 km north of Polozk, along the Polozk-Newel railway line.

On June 1, 1944, I learned that Alex Hory, the father-in-law of Marcel Reppel, had been interned at Dachau.

I was just about to depart for a ten day leave when the Russians began to attack on the front. All leaves were immediately cancelled, when I received a telegram from home, telling me that my wife was seriously ill, which depressed me even more. It was June 14th, 1944. On June 22, 1944, the Russians attacked near Polozk on the Drissa River, but they were well served because we were waiting for them.

On June 30, 1944, we left at 2:30 in the morning heading towards Polozk; the Russians were attacking from all sides and everything was in flames. We arrived at Parawuka on July 3, 1944, to ensure the relieving of the 205th Infantry division. They were at the edge of a forest.

On July 9, 1944 I wrote to my wife: "A heavy, black, murderous Sunday. I have a shrapnel splinter above the knee and splinter near my hand. The bread bag is tattered. I am 10 meters from the enemy in the trench, and the rifle is damaged."

One day we were at the Duna my friend Bretschneider and were in the outpost with the radio. The Russians bombed and attacked us several times. While they were 150 meters from us, the SG came out of our hole and was killed. Figer was wounded.

On July 15, 1944, we were in Lithuania near Dunaburq, and on Saturday, July 22, I wrote again to my wife: "I'm glad I'm out of Russia". On July 23 and 24, 1944, the Russians attacked us all day, three times with artillery bombardments. It was very hot and we had nothing to drink.

On July 15, 1944, we were in Lithuania near Dunaburq, and on Saturday, July 22, I wrote again to my wife: "I'm glad I'm out of Russia". On July 23 and 24, 1944, the Russians attacked us all day, three times with artillery bombardments. It was very hot and we had nothing to drink.On 5 August 1944 we were in Latvia, a beautiful region where we took a bath in the Duna, 90 km from Riga, and on 12 August we left by train for Riga.

On August 13, 1944, we arrived in Riga. In Riga there were beautiful churches and the bells rang. And on the 14th of August we left Riga by trucks towards Wenden in the North and Walk. The next day, supported by the stukas (German dive bombers), we routed the Russians.

On August 27, 1944, we were in Rewal, all the way north, and on the 31st of August near Dorpat. September 3 was a day of rest. On September 4, 1944, I returned to the front and on September 6 I was in the trenches with two other Alsatians in our group, in front of Dorpat (Estonia).

Wounded in Combat

On 8 September 1944 we received schnapps and wine. At 1 o'clock in the morning we were conducting an offensive on Dorpat, and a mortar grenade exploded two meters from me, followed by a shell which wounded my comrade Dinges from Worms.

The Russian planes flew over us and two other soldiers of my group were wounded. We had to remain in water filled trenches until the morning. Once again, in the morning, I was struck by shrapnel in the right knee, and at that point I was unable to continue. They took me to the rear, and on September 12 at 9.30 pm I was operated at the town center.

On September 14th, I was transported by train to Rewal, Estonia, where I was loaded onto a hospital ship. The ship left Rewal on September 16th with 1000 wounded on board. We were on the sea 3 days before arriving at the port at Swinemünde (port city in northwest Poland) on September 20th, 1944 at 9 am and we were immediately transferred by train to a hospital in Striegau (south-western Poland). I stayed at the Präparandie hospital from September 21st to November 25th.

I was well taken care of. Right away I sent a telegram to my wife, Jeanne, to come to see me. Unfortunately there was no longer a way of coming. The Americans were already in the Vosges mountains not far from the village.

I underwent two surgical operations in the right knee, followed by an infection (bursitis). Here are excerpts from letters I wrote to my wife during this hospitalization: October 6, 1944;

“The knee held but not moving well”. On 22 October 1944, "Do not hope for a leave in Alsace." On 30 October 1944," I am here in the eighth week and the wound is still open and still festers." On 10 November 1944; "A year's gone by since my last leave".

When my wound was finally healed, I no longer had leave to see my family. On Saturday, November 25, 1944, I left the hospital to be assigned to the Grenadier Ersatz Battalion 32. Upon arriving at the barracks I was immediately pronounced ready for service. I was sent to Teplitz-Schonau (Czech Republic) in South Sudland, and on the December 3rd, 1944 I arrived in the March Company at Zwickau-Schedewitz (Sudetenland).

I no longer received news from my family because of the battles in Alsace with the Liberators. The French had freed Colmar and the American army had crossed the Vosges mountains and were at Selestate, 8 km from Mussig.

On December 6th, 1944 I was again at the front near Steinau / Oder, and from December 27th, 1944 to January 9th, 1945 I was able to enjoy leave in Chemnitz (Germany).

Again at the Eastern Front

I was again sent to the front in January with a division of all kinds of people of all ages and none knew his neighbor. I had no friends. Meanwhile the Russians were advancing towards Germany.

|

| Column of German infantry |

First an ambulance took the wounded to Legnica (city in SW Poland). We boarded a train marked with a red cross so it wouldn't be bombed. I was first transferred to the hospitals of Friedland / lsergebirge, then to one in Ulm / Wiblingen where I was operated on. I was afraid, there were bombardments every night.

I was then transferred to Bad-Ditzenbach, and finally to Geislingen which was in the country where it was peaceful. Every night they took us into the cellars. It was at this hospital that I waited out the end of the war.

Everywhere they Germans were on retreat. There were two French soldiers who came to see us and we explained our circumstances, that we were incorporated against our will. May 5, 1945 was the Armistice and everywhere the bells rang and all cried for joy. The Alsatians and Lorrains were separated from the Germans and allowed to return home.

Return to family

After the war, Maurice and Jeanne would add two additional children to their family: Norbert born in 1946 and Bernadette born in 1954.

His beloved wife Jeanne died on November 20, 1999 at the age of 81. Maurice died on September 26, 2009, in his 94th year.

His son Norbert said his fathers words will remain forever in our memories, like a mighty desire for universal peace, "Nie meh ke Krieg"; Never again war!